Walt Schagen

7 min read

Quantum-Resilient Blockchain: Navigating the Threat Horizon

Date: January 13, 2026 Author: Walt Schagen, CTO

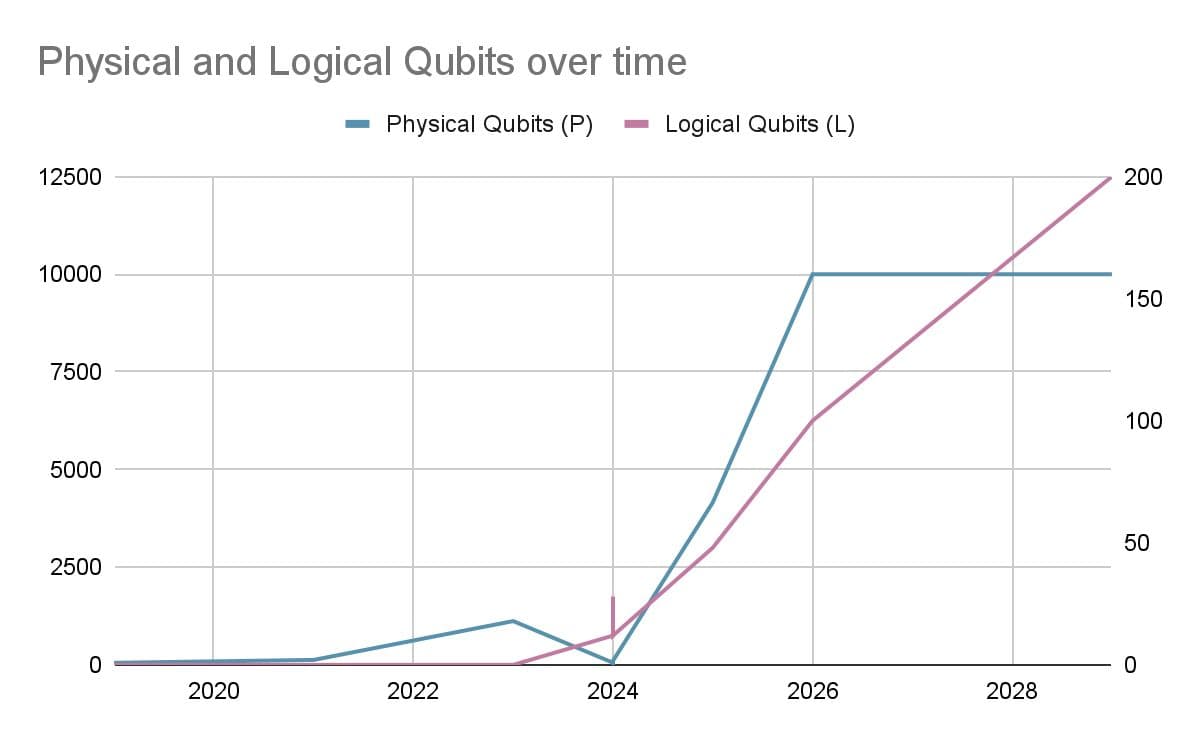

In the high-stakes intersection of blockchain, AI, and software development, the "Quantum Threat" is no longer a distant academic debate. As we move through early 2026, we are witnessing a fundamental shift from counting raw physical qubits to engineering stable, logical systems. For any project building on decentralized ledgers, understanding the delta between hardware progress and cryptographic thresholds is now a core requirement of risk management.

The primary evolution in 2026 is the divergence between Physical Qubits (P), the raw, noise-prone hardware, and Logical Qubits (L), the error-corrected units capable of executing complex algorithms. Current estimates suggest that breaking standard ECC-256 encryption requires between 4,100 and 6,100 logical qubits, though mathematical advancements continue to lower this barrier.

To understand the threat, one must understand the mathematical "hard problems" that currently secure the internet and blockchain networks. Current encryption relies on mathematical operations that are computationally cheap to perform in one direction but astronomically expensive to reverse -> the ‘one way street’.

The Discrete Logarithm Problem (DLP) & Elliptic Curves

Most blockchains rely on Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC). Unlike a simple linear equation where y = mx, an elliptic curve is a specific set of points satisfying an equation like y^2 = x^3 + ax + b.

Quantum Interference: How Shor’s Algorithm Wins

Shor’s Algorithm does not "guess" keys. It utilizes quantum interference at the wavefunction level. In a quantum processor, the state of the system is a superposition of all possible answers, each with a "probability amplitude" (a complex number with a phase).

A common misconception is that a quantum computer is simply a "faster" parallel processor. It is more accurate to view it as a machine that uses the physics of wave interference to compute.

Entanglement and the Global Wavefunction Individual qubits might seem like standalone instances of state. However, in a functional quantum processor, qubits are entangled. They do not exist as independent units; they form a single, joint wavefunction.

When running Shor’s Algorithm, the processor manipulates the "phase" of this global wavefunction. Through a sequence of quantum gates, the algorithm ensures that the probability amplitudes of incorrect answers (noise) undergo destructive interference: literally canceling each other out.

Meanwhile, the periodic sequences that correspond to the factors of a private key undergo constructive interference, amplifying the correct answer until it dominates the system. When we measure the qubits, the wave collapses into the correct private key with near certainty.

From a nanotechnology perspective, superconducting qubits (operating near 0 Kelvin) are notoriously volatile. You might expect a single qubit losing its state to cause a thermal "chain reaction" or widespread decoherence. Google’s Willow processor addresses this using Surface Code error correction.

Surface Code organizes physical qubits into a 2D lattice where "measure qubits" perform parity checks on surrounding "data qubits" to detect bit or phase flips without collapsing the quantum information. These error patterns are processed by real-time decoders that identify and "reset" faulty states before they can propagate across the system.

Physical vs. Logical: We group many "Physical Qubits" into one Logical Qubit. For a "Distance-7" code, you need roughly 49 physical qubits to represent a single stable logical qubit. Moreover, IBM’s “Gross Code” breakthrough allows them to encode 12 logical q-bits using 288 physical qubits, dropping the ratio to 24:1.

The Benefit: While it seems like a high cost (24 or 49:1 ratio), the benefit is an exponential reduction in error. Once we are "below threshold," adding more physical qubits doesn't add noise; it makes the logical state exponentially more stable.

Leakage Control: To prevent chain reactions, the lattice uses "Measure Qubits" to check the parity of neighbors without disturbing their data, resetting individual errors before they propagate.

A specific vulnerability relevant to entrepreneurs is the "Harvest Now, Decrypt Later" strategy. Malicious entities are currently intercepting and storing encrypted blockchain traffic. To a classical observer, this is noise. However, once a Cryptographically Relevant Quantum Computer (CRQC) matures, this stored data becomes transparent.

The "Exposed Public Key" Danger

In blockchain, your address is usually a hash (a one-way scramble) of your public key.

The risk profile has expanded beyond institutional research labs. By 2026, the focus has shifted toward the availability of quantum hardware to private actors and nation-states.

China (CAS/USTC): Leading in photonic quantum computing (e.g., the Jiuzhang series) and superconducting processors like Zuchongzhi-3. Their focus on high-speed random circuit sampling poses a specific threat to unstructured cryptographic problems.

Europe (Alice & Bob): Pioneering "Cat Qubits," which are inherently bit-flip protected. This architecture aims for a 200x reduction in hardware overhead, potentially allowing a smaller, buyable machine to reach decryption relevance.

Sovereign Clouds: With entities like IonQ and QuEra delivering on-premise hardware to national supercomputing centers, "Black Box" quantum attacks—where malicious operations are unmonitored by the manufacturer—have become a credible threat to high-value RWA (Real-World Asset) bridges.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)—the global referee for encryption—has finalized the first quantum-resistant algorithms: ML-KEM (key exchange) and ML-DSA (signatures).

The Performance Tax & Optimization

Lattice-based cryptography is computationally efficient but has a massive "Data Tax."